Vanishing People: the Population Crisis

for us to solve the challenges ahead, there needs to be an "us"

*Originally published on Pirate Wires*

When asked about the source of his inspiration, Elon Musk appeals to a refreshingly simple philosophy: we must protect and spread the rare spark of human consciousness. In this light, his titanic ventures make sense. He pursues complex problems few would dare go up against, and for this reason what worries him should utterly terrify the rest of us.

Alongside his other interests, population collapse might seem insignificant. After all, you’ve likely been told for years that overpopulation is a pressing concern for humanity. Let me shatter this notion — you need to fear the opposite. We are standing on the brink of a catastrophic global population collapse.

For those tackling civilization-scale problems, the Great Filter provides a conceptual challenge — an outstanding question as to why the universe isn’t buzzing with life. From this perspective, Elon’s efforts are obvious attempts to eliminate potential filters that threaten a blossoming civilization, like runaway climate change, nefarious artificial intelligence, or being stuck on Earth during a cataclysmic event.

But among our greatest existential threats, population collapse is unique in that it lacks a noticeable, immediate pain for us to rally against. There are no wildfires or smog-filled skies to capture the imagination of our journalists or filmmakers, thus inspiring no individual action. It is precisely because of this attention void that I believe we encounter the true Great Filter. The end of civilization will not stem from the fiery consequences of our wildest inventions, but from the growing dearth of our most essential, and cherished creations — children.

“This is the way the world ends. Not with a bang but a whimper.”

- The Hollow Men, T.S. Eliot

The global population is expected to peak around 2100 at 10.9 billion people. At first glance, this seems like a far off problem, and many would laugh if you even called attention to it. But the change in growth rate tells a different story, having peaked in 1968 at 2.1%. This statistic is much more important. Critically, it is not the number of people that matters most, but the number of young people. Furthermore, the ratio between the young and old in a society dictates its future.

Compared to the elderly, young people both produce more things and buy more things. Because of this, they drive the majority of an economy, growing GDP and generating tax revenue. Throughout your adult life, you’re building stuff, buying goods, and investing in the capital markets, but the moment you retire this stops. You’re no longer producing anything, you reduce spending, and your investments are exchanged into cash or Treasury bills.

Now, it’s one thing when this age ratio flips in a single country, like Japan, but consider for a moment what it means if the rest of the developed world follows in unison. Gradually, then suddenly, the global economy faces a crisis. Consumption begins to drop all together and the net flows into capital markets reverse. Less consumption means less aggregate demand, triggering a global recession and crippling the still-developing world reliant on these markets. On top of this, a reduction in labor force, in perpetuity, flywheels the consumption collapse and makes global growth incredibly difficult. Meanwhile, the shrinking fraction of young people must shoulder the heavy burden of a growing elderly population. Less tax revenue forces less expenditure, just as the aging population demands it. From a fiscal perspective, this is increasingly untenable for even the wealthiest nations.

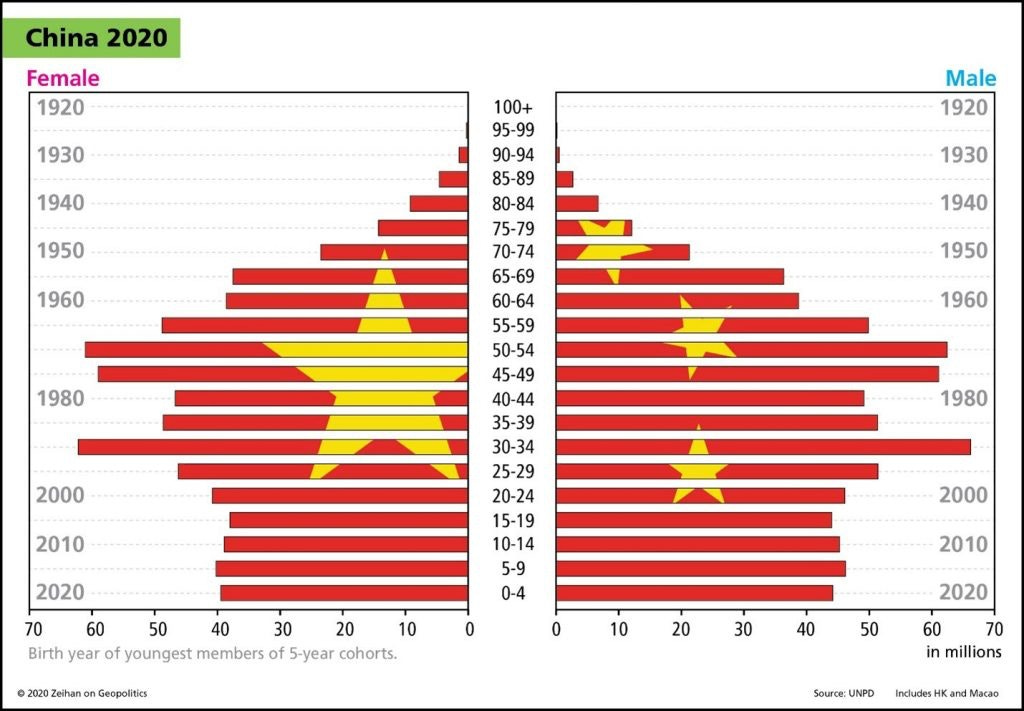

To determine the stability of a society’s demographics, we use a population pyramid, or a chart taking a snapshot in time and segmenting by age and sex. A growing population has a wide base (more children) and a thin top (less elderly). Consider China.

In 1950, due to various policies and the global post-war boom, the country experienced a surge in population growth. In the 1970s, post-Mao reform caused a second, larger increase unlike anything the world had ever before seen. Facing violent growing pains, Chinese officials instituted the One Child Policy, illustrated by the shrunken bar in 1980.

Now, let’s fast forward to today:

Demography is not destiny, but it’s pretty damn close. China’s rapid rise is a product of the bulk of its population, born in the late 20th century, reaching their prime working years and integrating into the global economy. In 2016, China scrapped the One Child Policy for the Two Child Policy, then again in 2021 for the current Three Child Policy. Today, the median age in China is now 38.2 years old, higher than the United States, but still far behind Japan at 48.4 years old. This is the future awaiting China.

Since the 1990s, when the majority of their population was in their prime productive years, Japan’s GDP has flatlined, even with negative interest rates. As a greater percent of the population ages, a larger amount of resources are committed to taking care of the elderly, both in the form of capital and labor.

Today, the Japanese are not alone.

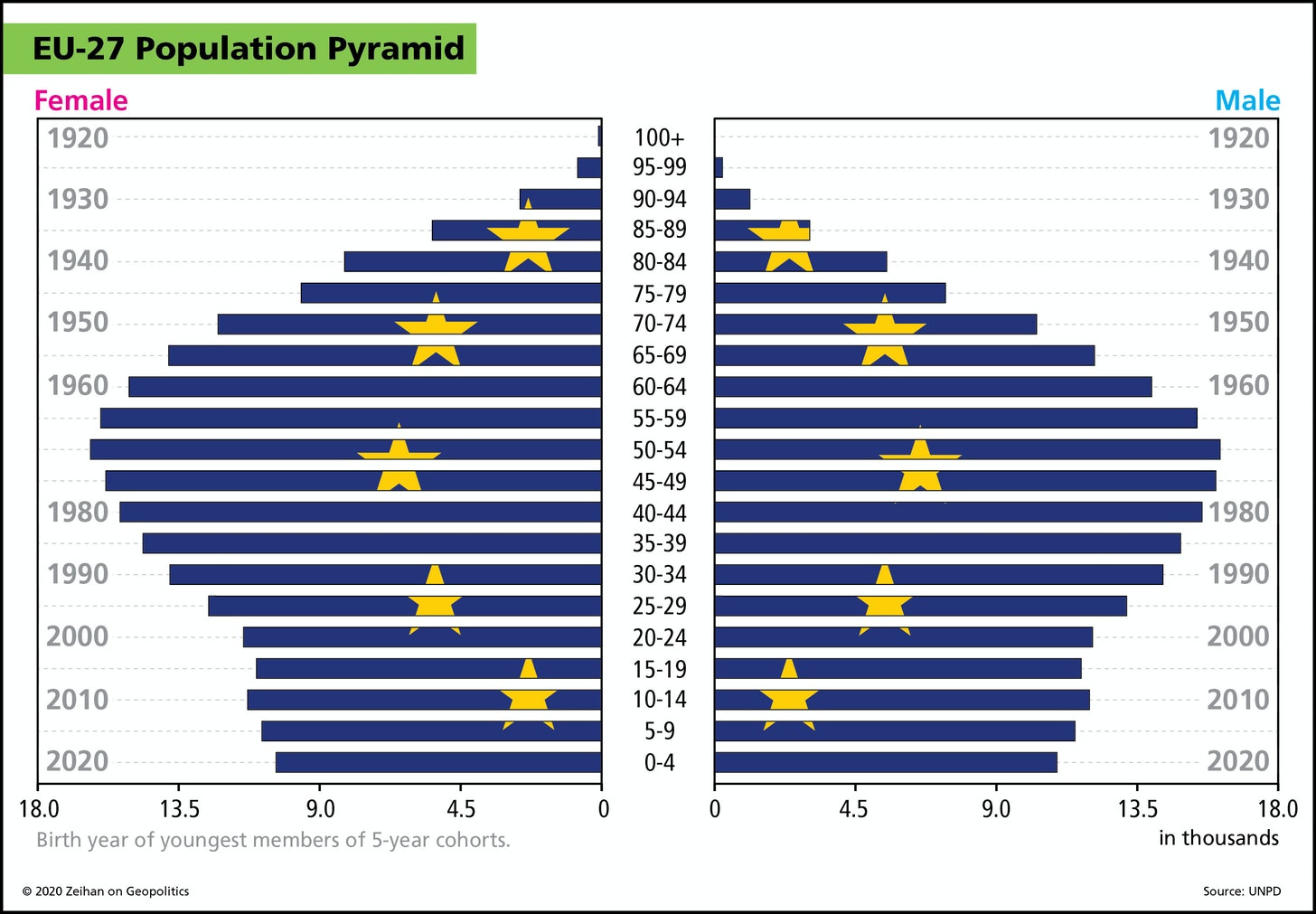

The developed world is old. It has also stopped having children. When trying to understand this problem, a key measurement to pay attention to is fertility rate — anything under 2.1, or rather the children born per woman that exceeds both parents, equates to a net decrease in population after accounting for childhood death.

For perspective, the fertility rate of Europe today stands just below 1.6. This means 100 grandparents beget 80 parents who then have 64 children. Europe’s population is in terminal decline — a rich cultural history literally vanishing, person by person, before our eyes. Studies suggest that the leading causes of decline are education, urbanization, access to contraception, and many other factors related to wealth and human rights, particularly for women. Herein lies the demographic paradox: as a country becomes more advanced, its fertility rate plummets.

In Japan, we see a glimpse of Europe’s future. The combined GDP of the EU remains lower than its 2008 high, and a shifting ratio of young and old will force drastic reform of their progressive social programs.

The population crash is not confined to the developed world. Brazil, Russia, and China were collectively favored to be productive powerhouses throughout the 21st century, but today their demographics look a lot like Canada’s, a country that has also forgotten how to have children.

Capitalism’s great achievement was allowing us to acquire resources with dollars and not blood, but a gloomy demographic future precludes this. The Russian population, for example, is rapidly aging, which presents grave and obvious national security concerns. These are their workers and soldiers, all critical to any military engagement. Though, their population pyramid tells us that in a decade they’ll have a fraction of their current young fighting force. Any long term plans have been accelerated, or forfeited entirely. Does this partly explain Russia’s invasion of Ukraine? Perhaps even more concerning, what does the war in Ukraine foretell further east? The Chinese population is expected to peak in 2030.

While nearly all fertility rates are in decline, the decline is not equally distributed. Some nations, even in the developing world, show a glimmer of hope: Turkey, France, India, and the United States.

Turkey and India present an economic future powered by rising demographics, while France and the United States are financially stabilized by immigrant fertility, family policies, and a young generation of voracious consumers.

This is not enough.

The fertility rates of India and Turkey have plummeted, as expected with development, and while France and the United States have retained their fertility rate, buoyed by immigrant populations, it’s not at all clear that we should expect further success in this regard.

In the first place, we’ve already seen backlash against immigration in Europe and the United States, and Japan is still something very close to a closed society. In an increasingly volatile economic and security environment, do we really believe any nation facing a grave fiscal deficit will welcome more low-skilled immigration? But even if we do manage to embrace more immigration, it only kicks the can down the road from a civilizational standpoint. In a generation, immigrants revert to the local fertility rate.

That said, these countries have at least secured what the rest of the developed world has not — time. My hope lies not in their long term prospects, but in their capacity to learn from the crumbling populations around them before it’s too late.

What I’ve presented to you is a projection of global economic recession and political volatility. If you’re not moving forward, you’re moving backward, and a country with no people has no future. In this demographic environment, capital will become scarce, fleeing to markets that provide fleeting, stable growth for the time being, movement that will ultimately prove futile if nothing changes. I suspect the early burden of demographic pressure to fall on the developing world first, which faces the most dire consequences of calamities like climate change or war, and which will receive little foreign investment, limited ability to immigrate, and shrinking consumer markets to sell their goods. In contrast, developed nations will become retirement homes. Increasing amounts of capital will go towards supporting the elderly and, for the first time in centuries, we’ll be fighting over a diminishing economic pie.

There may be some among you who find this collapse appealing. Simply, less people means there’s more to go around, goods will become cheaper, the skies will clear, and the droughts will end. But just as Malthus was wrong before, this de-growth mindset fails to recognize humanity’s ability to innovate, as well as the horrific repercussions of such regression. Everything around you is the product of growth, and the solutions to its consequences are also dependent on our continued progress — both on Earth and across the stars. History is riddled with periods of population decline, but I fear civilization may not survive another one intact, particularly not a collapse of this magnitude.

For example, consider the difficulty of solving climate change if we are in a spiraling economic collapse, flanked by labor shortages, political turmoil, and conflict. Moreover, nation states at the precipice of power would feel increasingly cornered as everything shrinks around them. This stymies the global cooperation necessitated by mankind’s existential challenges.

In some apparent awareness of this looming catastrophe, Europe has become a lab for fertility rate experiments.

We begin by looking at Northern Europe, famed for its wealth, egalitarian values, and leisure time. Surely, a case study on the limits of what’s possible.

Across the Nordic countries, pro-Natalist policies aimed at boosting fertility rates have failed, and for some, now sit at record low levels. This is in spite of exceedingly generous family policies, like a year or more of paid parental leave and heavily subsidized daycare. France has seen a small boost from a similar model, but at the cost of billions the fertility rate remains below replacement.

Elsewhere in Europe, we see more heavy-handed attempts to turn things around. Hungary is spending roughly 5% of their GDP on boosting their fertility rate, which was among the lowest in Europe at 1.23. To their credit, income tax exemption, cash payments, and emphasis on “socially conservative” values have provided a bump in fertility to 1.48, but it remains unclear if these policies caused people who would otherwise not have children to do so, as opposed to simply accelerating existing family plans. Time will tell, yet already this approach has caused a stir among governments able to implement such strategies, and equally so in countries that reject these, and other tactics entirely.

This all points to the elephant in the room.

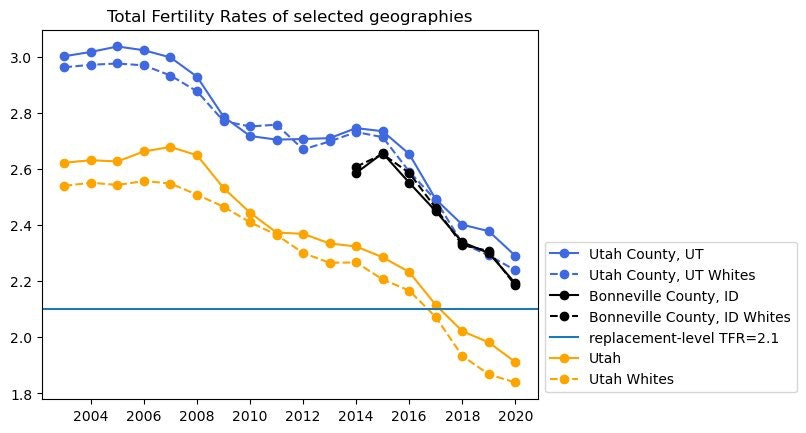

Evidence suggests that there is no feasible economic policy alone that provides the necessary velocity to escape terminal population decline. Hungary’s policies lean towards the notion that perhaps the solution eludes us because it is by nature illogical, composed of things difficult to measure. Broadly, I believe these intangible factors fall into two major groups, though I find them increasingly blurred: religion and political fervor.

I won’t go into each religion respectively, but I’ve selected Mormonism because it is commonly associated with large families. While still higher than secular groups, the Mormon fertility rate is dropping precipitously. Various other religious groups follow similar, albeit less dramatic trends.

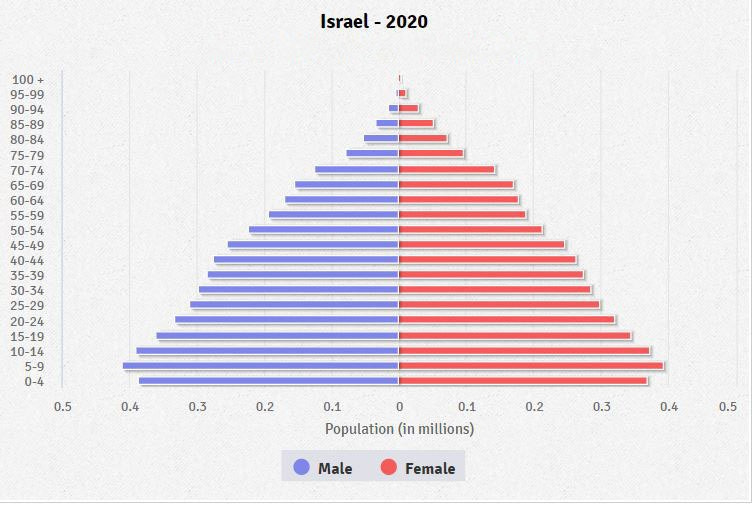

In a similar vein, politics appeals to a belief beyond one’s self. In many cases, this manifests as nationalism, or intense support for one’s country. We see glimpses of this in Hungary, yet the power of nationalism becomes truly magnified when coupled with religion. Israel remains a steadfast example of the bonded pair.

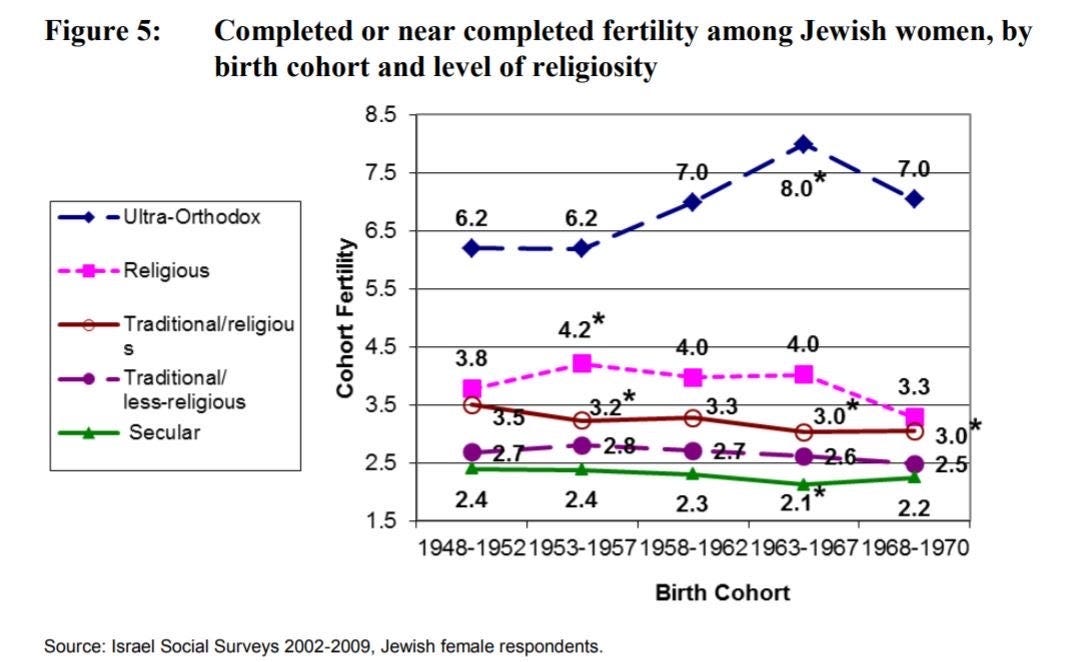

With a fertility rate of 2.9, Israel bucks the global trend. While it doesn’t have the population to make the necessary dent on the global economy, it provides a fascinating study of the impact of culture on population growth. Jewish diaspora conforms to expected sluggish trends, but we don’t see that in Israel. Segmenting further provides some insight.

As expected, religiosity correlates with fertility, yet, surprisingly, even secular Israeli women have remained above the fabled 2.1 fertility rate. What’s more, they’ve been able to achieve this despite having among the highest levels of women participation in the labor force. This defies explanation, but I will attempt one anyway. Israel exemplifies asabiyyah, or rather the cohesive force that bonds a people, grown stronger by harsh conditions. Israelis know conflict all too well, and I believe this is reflected in an innate sense of duty to have children and prolong the vitality of their state.

This points to a worrisome conclusion. If it is indeed this strong social cohesion that can reignite fertility rates, let’s be honest: liberal democracies face an uphill battle. And even if I’m incorrect, the morally repugnant, but obvious solutions to fertility are not out of the question for our authoritarian adversaries. While the West squanders its flickering demographic and economic power, others will likely enforce coercive measures like something out of Handmaid’s Tale. Demographic control is nothing new. The rules of the future will be written by nations with the populations to back them up. The stakes could not be higher.

A saving grace of humanity is our ability to innovate, particularly in times of crisis. First, Sahil Lavingia makes a suggestion.

At face value, you can see the rationale behind synthetic wombs, but I do have some concerns. I believe this idea fails to appropriately recognize the bond between mother and child, both physical and emotional, nor does it help with the 18+ years of child rearing. I don’t like this solution, but my queasiness alone should not prevent further research, as I do recognize that this would help many women.

In contrast, Katherine Boyle presents a theory that aims to attack one of the core underlying causes — urbanization. She believes that the collapse in the fertility rate stems from the decline of multi-generational households as 20th century Americans moved into cities. Having extended family members to help with child rearing makes a big difference, but this requires more space. This is where, she suggests, permitting remote work from rustic locations can boost fertility rates — a rural renaissance powered by Starlink. Upon deeper analysis, Katherine’s focus on physical space being a primary driver becomes more compelling. Evidence suggests that as home prices rise, fertility falls. In the United Kingdom, a 10% increase in housing costs led to a 1.3% decline in birth rates. Building more homes may boost fertility.

In truth, the solution to the population crisis is no doubt multi-faceted and will be unique to different societies, consisting of a mix of the ideas shared above and new ones yet to be explored. What makes this problem so sinisterly difficult is how it came upon us, sneaking behind and dealing a critical strike. We’ll slowly bleed out if we pay the wound no attention, but, more importantly, it makes fighting our current battles much more difficult. In our strife, we must not fall victim to the siren calls of collectivist ideologies that decry the growth-oriented, free markets that have built the modern world, and with which we might one day grow so numerous and colonize the stars.

Clean energy, safe artificial intelligence, and space exploration are achievements to be made in humanity’s near future. But fertility is not an engineering problem that Elon Musk can solve alone (no matter how hard he tries). Having children is a literal investment into the next generation, and, even more so, a vote in the defense of our liberal values and freedom.

It’s poetic that pushing past the Great Filter relies not on a singular moment, but on the continued product of healthy relationships shared between people. That it demands individual action, in spite of logic, to prevail over impending conflict that threatens the proliferation of human consciousness.

The choice is ultimately yours, but there’s only one option that will save us. It’s not even a new idea. We just finally have to take it seriously: Make Love, Not War.

-Ryan McEntush

Thanks to @PeterZeihan and @OurWorldinData for statistics and charts.

This is a really good article that I really enjoyed from a statistical perspective. It's full of facts, figures, and logical arguments.

However, I wish people would spend more time talking to those that are either hesitant or don't really want to have children. There's also a huge fear that the only people who care about the demographic crisis are a) men, who don't have to experience child birth or socially deal with its consequences and b) very very wealthy people who are seen as wanting more humans to exploit.

Honestly, this is a fear that I have. I think very few "pro-natalists" want to make a good emotional argument for why one should be interested in having as many kids in what might feel like precarious circumstances.